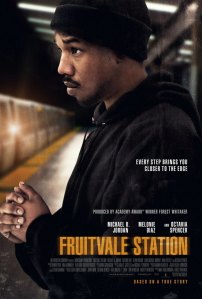

5*

Director:

Ryan Coogler

Screenwriter:

Ryan Coogler

Director of Photography:

Rachel Morrison

Running time: 85 minutes

Fruitvale Station is not a film about race and immediately accessible to a very wide audience. The story is about the beauty, the frustration, the dreams, the indecision, the memories and the love embedded in one man’s last day on earth. With mesmerising performances, an intimacy that is utterly compelling and a main character that is far from perfect but does his best until his past catches up with him in the most tragic way imaginable, this is one of the best débuts I have ever seen.

The director is Ryan Coogler, who shot the film in 20 days only a few weeks after his 26th birthday. His story is small enough to focus on the details of Oscar Grant’s last day, based on the real events that took place New Year’s Eve 2008 and early on New Year’s Day 2009 at the Bay Area Rapid Transit station of Fruitvale in Oakland, San Francisco. Its more ambitious moments, namely a handful of unbroken takes, don’t draw attention in a way one would have expected from an inexperienced filmmaker. They never stand out from the rest of the production, and perhaps the reason is the dynamite performance of the actor who plays Oscar, Michael B. Jordan.

The film is bookended by the events of New Year’s Day, and the opening scene is clearly shot with a cellphone camera or some other handheld device with low-quality images. The reason for this is only explained at the end, although the documentary quality accurately indicates the origins of the story with actual events. What we get during the film, then, is New Year’s Eve, which not only builds towards the evening’s midnight celebrations in San Francisco but also the birthday dinner of Oscar’s mother, Wanda (Octavia Spencer).

Over time, we learn a great deal about Oscar’s life through his interactions with those closest to him: his girlfriend, his daughter, his mother and his tight-knit group of friends. One of them is Cato, played by Coogler’s brother, Keenan. Cato works at the Farmer Joe’s Marketplace supermarket in Oakland, where Oscar was recently fired for turning up late to work once too often. The two are friends, but when Oscar’s attempts to get rehired by the otherwise affable manager are unsuccessful, he fails to mention this to Cato, instead telling him he will start again the following week. Oscar, whose tattoo spells out “Palma Ceia” (one of the gangs in the neighbourhood of Hayward) and who was recently caught cheating on his girlfriend, is actually a very vulnerable individual, and Coogler reveals his character with details that are surprising short but impressive.

Such moments include a flashback to a year earlier when his mother had visited him in prison, and another very intelligent add-on when he sees an ownerless dog, strokes it, before seconds later hearing a yelp from the highway, where he picks up the dog and carries its bloodied body back to the side of the road. Of course, this anticipates the events at the end of the film by showing us how quickly a creature can go from smiling and energetic to still and lifeless. But it is nonetheless (perhaps therefore) intensely poignant and may even move us to tears.

The seemingly mundane, within the context of a single day and given our knowledge that all of this is leading up to something terrible, takes on extraordinary meaning, and Coogler should be given all credit for imbuing his story with both energy and affection that always come across as entirely believable. Even Oscar’s daughter, Tatiana (Ariana Neal), is a natural in front of the camera and cannot be faulted for a single false move or response.

Fruitvale Station shows us the story of one man who has his faults but is totally likeable throughout and whose life is filled with some of the experiences and feelings we all share, conveyed with the utmost sincerity. His beautiful smile, his love for his daughter, his aggression in the face of injustice and desire to change his life for the better are all attributes we admire. This is not the story of someone up against the system, but rather about someone up against himself and especially his past.

It is difficult to believe this was Coogler’s first feature film. Especially the slightly risky move of presenting one of the final scenes without showing us the face of its central or focal character is jaw-droppingly astounding, bringing with it the necessary uncertainty that the scene calls for. I for one cannot wait to see what Coogler does next.